19, 20 and 21 October 2024

Visit of the descendants of the Johnston and Gwilliam families

Rubescourt (Somme)

Le Frestoy-Vaux, Maignelay, Coivrel, Beauvais (Oise)

Pantin (Seine-Saint-Denis)

This visit having been postponed since 2020 because of the pandemic, we finally had the honour of welcoming Colin Johnston and Bradley from Melbourne (son and grandson of F/Sgt. Eric L. Johnston) as well as Erin Sharp (daughter-in-law of F/Sgt. James P. Gwilliam) from Sydney who was accompanied by her niece Tara. These families had made the long journey from Australia to try to shed light on their fathers' adventures.

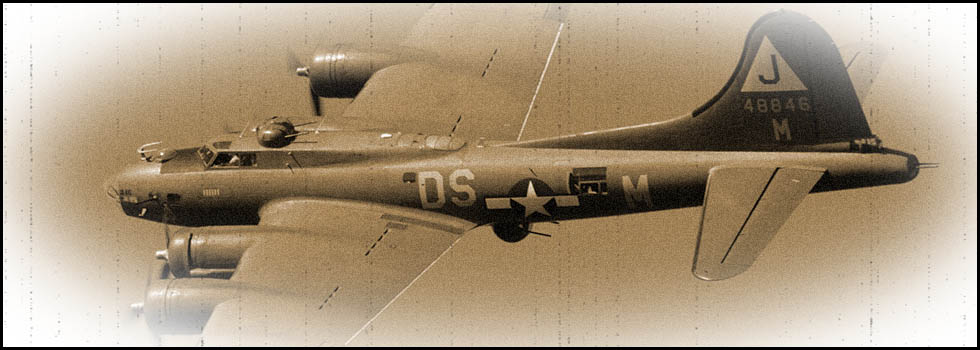

Their visit began in the morning in Rubescourt (Somme), a small village of 135 inhabitants, near to where the Halifax bomber MZ692, RAF 78 Squadron, crashed on the night of 22 to 23 June 1944.

Mme Chantal Desprez, the village's mayor, members of the municipal council and many people interested in the history of the event and the arrival of these Australian families welcomed us. Two vintage vehicles (a Jeep and a Dodge) then took us to the crash site in a pasture near la ferme de Pas.

To the great surprise of our Australian friends, Mr Moreau, the owner of the site, handed over pieces of aluminium from the bomber that had been found over the years.

Mr Moreau handing a piece of the Halifax to Colin Johnston.

Erin Sharp, also holding another piece of the aircraft.

Souvenir photo with some of the descendants of the families who sheltered the airmen.

Colin driving the Dodge that took us back to the heart of the village.

This was followed by a reception at the town hall, where Mme Chantal Desprez and her council invited us to drinks.

One of the villagers was moved to hand over a dictionary that had been found among the wreckage of the plane in 1944 and kept ever since.

In the afternoon, our next stop was Le Frestoy-Vaux, a village divided into three parts: Le Frestoy, Vaux and Le Tronquoy. It was on the territory of this village that three members of the crew, Eric Johnston, James Gwilliam and pilot Robert Mills, fell separately by parachute. At Le Frestoy, the descendants of the Dufeu family showed us the farm where Robert Mills had stayed with their grandfather.

The barn next to the farm where Robert Mills was hidden.

Photo with descendants of the Dufeu family in front of the former family farm.

We then moved on to Vaux but, alas, the slate-roofed house on which Eric Johnston had landed no longer exists and has been replaced by a new house.

Finally, Le Tronquoy. It was near this hamlet that James Gwilliam landed in a tree before being put up temporarily in a small house. The owner of the farm gave us the location of le bois du Tronquoy, where the airman had hung for some time from his parachute entangled in the branches.

Bradley, Colin, Tara and Erin near Le bois du Tronquoy.

One of the houses near the farm where James Gwilliam was probably taken in.

Via Le Ployron, where unfortunately the ‘75’ level crossing no longer exists, as does Germaine Carlier's house, we reached Maignelay, where we were joined by several descendants of the families who had come to the aid of the airmen in the various surrounding villages. In addition to the Dufeu family, the Levasseur, Floury, Duriez, Horb and Lherminier families were represented. We visited the former home of Pierre Gager, who provided shelter to Eric Johnson and Robert Mills.

In front of Pierre Gager's house

At each place, explanations were given, translated into English by our friend Franck Signorile.

Last stop of the day: Coivrel, first in the cemetery for a particularly emotional moment in front of the grave of the Creton couple, owners of the café that gave shelter to the Australian airmen. Guy Pieronne, their grandson, who should have been with us, had asked Colin Johnston to make a symbolic gesture of great importance to him.

At the end of July 1944, the Creton couple let the airmen go after having forged a strong bond of friendship with them. The four Australians were to join another group of Resistance fighters and then be flown back to England that same evening. They had agreed before their departure that a coded message would be broadcast on the BBC, proving that they had arrived safely in London. That evening and in the days that followed, the Cretons listened to the programme "Les Français parlent aux Français" on Radio-London, but the message was not broadcast. It never was. The reason was that the airmen had fallen into a trap and had been arrested by the Germans.

The Cretons died without knowing what had happened to their protégés.

80 years later, in front of the graves of Mr Pieronne's grandparents, Colin Johnston, overcome with emotion, was finally able to utter the coded phrase that they would so have liked to hear on the BBC: "Kings are crowned".

We then wandered through the village streets, discovering the various houses where Robert Mills, Keith Mills, Eric Johnston and James Gwilliam had taken refuge.

First up was the former home of Paul Omnès. According to Eric Johnston's recollections, it was at the back of his house that the photo of the airmen with their helpers was taken before they left Coivrel at the end of July 1944. The current owner of the house kindly allowed us into her garden to reproduce, 80 years later, a photo similar to the one taken in 1944.

In the garden of the Paul Omnès house,

the Horb, Lherminier and Dufeu families with the Australians.

We then stopped in front of the former café-grocery that was run by the Creton family during the war. The façade has changed little, except that it is no longer a café. Surprised but delighted by this unusual visit by our Australian friends to their usually quiet village, the owners exceptionally allowed them to visit the inside of their house.

After a stop at the war memorial, where a wreath was laid by the municipality and a minute's silence observed, we were invited to the town hall by Mrs Aline Larue, mayor of the village, and her municipal council, where a reception was organised.

The town hall was also the school where Fernande Horb lived and taught, and where she and her husband helped the airmen. The multi-purpose hall where we gathered was in fact her classroom. An exhibition of photos and documents, prepared by the municipality, was on display.

In the presence of Patrice Fontaine, departmental councillor and mayor of Le Frestoy-Vaux, Mme Chantal Desprez, mayor of Rubescourt, descendants of the families who came to the aid of the airmen and many friends, Aline Larue, after welcoming our Australian friends and all those present, declared: "We are bringing to light a painful part of our village's history, but one that does us great honour....".

Patrice Fontaine said a few words, followed by a description of the Australian airmen' adventure. This was followed by a message from Guy Pieronne, grandson of the Creton family, who was unfortunately absent.

An emotional Colin Johnston then took the floor, with Franck Signorile translating into French:

On a more personal note from me to Guy Pieronne, who could not make it today, Merci, merci beaucoup".

Erin Sharp also expressed her emotion by paying tribute to the families who had helped the airmen.

I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to Franck Signorile and Dominique Lecomte for their dedication in researching this important historical event. Thank you".

This intense day ended with drinks and a profusion of cakes and other treats offered by the municipality. This moment of conviviality was the occasion for many exchanges and sharing between all.

On the left, Mrs Aline Larue, Mayor of Coivrel.

Descendants of the families who sheltered the airmen surround our Australian friends.

On 20 October, we went to the road leading from Chepoix to Breteuil, where the four airmen had been captured by the Germans after being betrayed. Then on to Beauvais, on the site of the former Agel barracks where they were held. All that remains today is a memorial.

On 21 October, we travelled to Pantin to meet Pierre Gernez, secretary of the Association des Amis du Musée de la Résistance nationale de Seine-Saint-Denis, and Cynthia Beaufils, head of the Pôle Mémoire et Patrimoine at the town of Pantin. They were accompanied by an interpreter and a number of journalists. With permission from the SNCF, we were given access to the 'Quai aux Bestiaux' alongside the railway tracks. This historic site is usually private and off-limits to the public. It was here, on 15 August 1944, that the airmen, among more than 2,200 deportees, boarded the convoy bound for the Buchenwald concentration camp.

An exceptional, emotionally-charged visit.

"When they came back to Australia, nobody believed them. They didn't have tattoos and normally airmen should never have gone to concentration camps" said Erin.

The day ended in a room at the town hall, where Franck presented his research into deported Allied airmen.

A few days earlier, Colin and Bradley had visited the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany.

Colin concluded: "The whole visit was a mixture of astonishment and extreme emotions such as excitement, happiness and sadness. There's no doubt that we filled in the blanks, even more than I thought possible".