22/23 June 1944

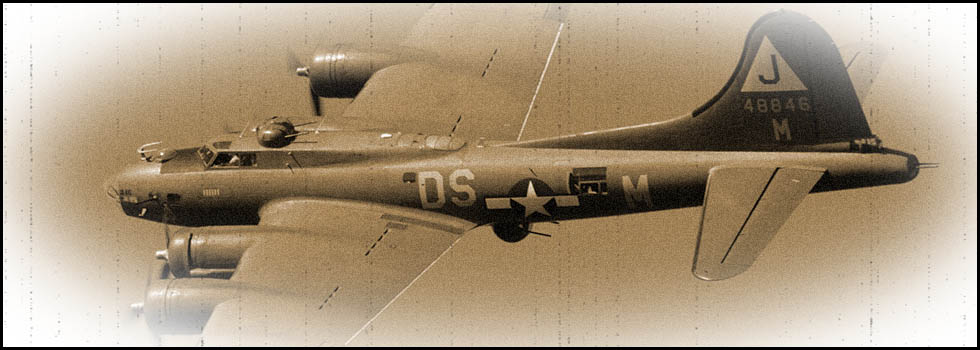

Handley-Page Halifax MkIII MZ692

EY-P

RAF 78 Squadron

Rubescourt (Somme)

Copyright © 2024 - Association des Sauveteurs d'Aviateurs Alliés- All rights reserved -

En français ![]()

During the night of the 22nd to 23rd of June 1944, 221 aircrafts of the Royal Air Force were tasked with bombing the railway infrastructures at Laon and Reims.

Taking part in this night raid were 24 Halifax aircrafts from 78 Squadron. They took off from RAF base in Breighton, Yorkshire. The target of the Squadron was Laon. Among them was Halifax Mk III MZ692 with a crew of seven airmen : six Australians and one Welshman. The aircraft was brand new and it was its first and also last mission.

The crew :

|

P/O Robert Neil MILLS |

Pilot |

20 |

RAAF |

|

Sgt. Charles Henry. WRIGHT |

Flight Engineer |

19 |

RAF |

|

F/Sgt. Keith Cyril MILLS |

Navigator |

20 |

RAAF |

|

F/Sgt. Ian Rossell Caple INNES |

Bomb aimer |

22 |

RAAF |

|

F/Sgt. Eric Lyle JOHNSTON |

Wireless operator |

21 |

RAAF |

|

F/Sgt. Douglas Reeves FODEN |

Mid-upper gunner |

19 |

RAAF |

|

F/Sgt. James Percival GWILLIAM |

Rear gunner |

22 |

RAAF |

Once over the target, the bombardment from an altitude of 11,000 ft proved to be fairly accurate, although it also hit the lower part of the town, which had already been badly hit by previous raids.

After dropping its explosive and incendiary charges, Halifax MZ692 turned and headed for the return flight to England. Shortly afterwards, Douglas Foden warned the pilot over the intercom that there was an enemy aircraft below. The pilot tilted the aircraft to the left, then to the right, allowing the crew to scan the night sky. Nothing ! Then, 12 minutes into the flight after leaving the target area, disaster struck. With no warning, the Halifax was suddenly hit by fire from a Junkers-88 attacking from below. Flaming fuel poured from the Halifax's left wing, producing a long trail of fire.

Wireless operator Eric Johnston did not want to jump into the unknown in the middle of the night. He asked the pilot to try to extinguish the flames in the engine by diving the aircraft. This attempt proved unsuccessful. The pilot, Robert Mills, gave the order to bail out from the aircraft, which had become out of control.

One by one, the seven crew members evacuated the Halifax in distress, which finally crashed in a pasture near la Ferme de Pas, in the village of Rubescourt (Somme).

During the same raid, Squadron 78 also suffered the loss of Halifax LK840, which crashed in Quinquempoix (Oise).

After hitting the ground, Sgt. Charles H. Wright remained hidden until the early hours of the morning before heading for a house where a woman and her son gave him food and civilian clothes. He decided to leave after an hour, as the family was not very reassured by his presence, and took a rest in a field. He then approached a farmhouse, where he was welcomed by the owners, but less than 10 minutes later, two lorries loaded with German troops arrived and captured him. He was imprisoned in Germany, first in Stalag Luft 7 until January 1945, then in Stalag IIIA in Luckenwalde, where he was liberated by the Soviet Army in April 1945.

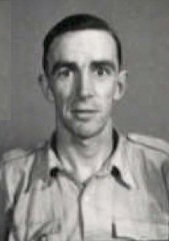

F/Sgt. Douglas R. Foden landed in a wood near Méry-la-Bataille. He was unable to hide his parachute which was caught in the branches of a tree but managed to conceal his harness and Mae-West. After waiting for dawn, he decided to head south and met a Frenchman who asked him if he spoke English. This Frenchman, Marceau Porquier, took him home (probably to La Neuville-Roy) where he stayed until the Liberation in early September 1944.

F/Sgt. Douglas R. Foden (NAA)

F/Sgt. Ian R. C. Innes, who lost his flying boots during his parachute descent, landed in the backyard of a café smashing empty bottles but nobody suspected his presence. He got rid of some of his equipment, left his parachute tangled up in barbed wire and went off to hide in a haystack. At dawn, he spotted a farmer and his daughter in a cart on their way to milk some cows. In school French, he explained that he was an airman and needed shoes. The farmer left and soon returned with some food, a bottle of wine and... a pair of boots. Then they went their separate ways.

F/Sgt. Ian R. C. Innes (NAA)

On 26 June, Ian Innes, still in his uniform, reached a wood where he met a 70-year-old woodcutter, Pierre Hériot, who took him to his home in Lataule. Fed and given shelter for the night, he set off again the next morning, dressed in civilian clothes, with the intention of reaching the Swiss border.

Passing through Compiègne, he crossed the heavily guarded bridge over the River Oise with local workers. He reached Soissons (Aisne), then Montépreux and Mailly-le-Camp (Marne), where he made contact with the Resistance.

At the end of July, he passed through Troyes (Aube) where he met a team from the British secret services responsible for supporting the Resistance, who promised to fly him back to England. As time went by, this did not happen. He decided to continue his journey alone towards the Swiss border and reached Champlitte (Haute-Saône). Crossing the border proved impossible, so he tried to reach the advancing American forces. In the meantime, he joined an SAS unit and took part in attacks against the enemy as a machine-gunner in a jeep.

On 31 August, guided by members of a Maquis, he finally managed to reach the American lines. On 6 September 1944, he was repatriated to England.

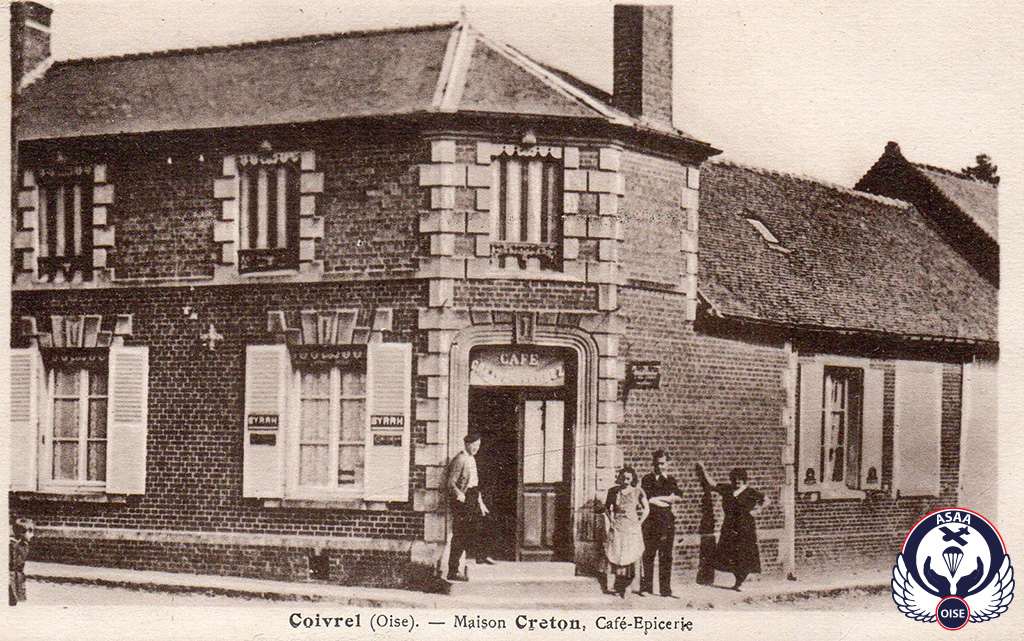

After landing near the crash site of his aircraft, F/Sgt. Keith C. Mills wandered for several days, helped here and there by patriots who came to his aid (places and people unidentified). On board a cart, he was finally taken to Coivrel where he stayed with the Creton-Tempez family, who owned a café, while awaiting the next stage of his escape.

F/Sgt. Keith C. Mills (NAA)

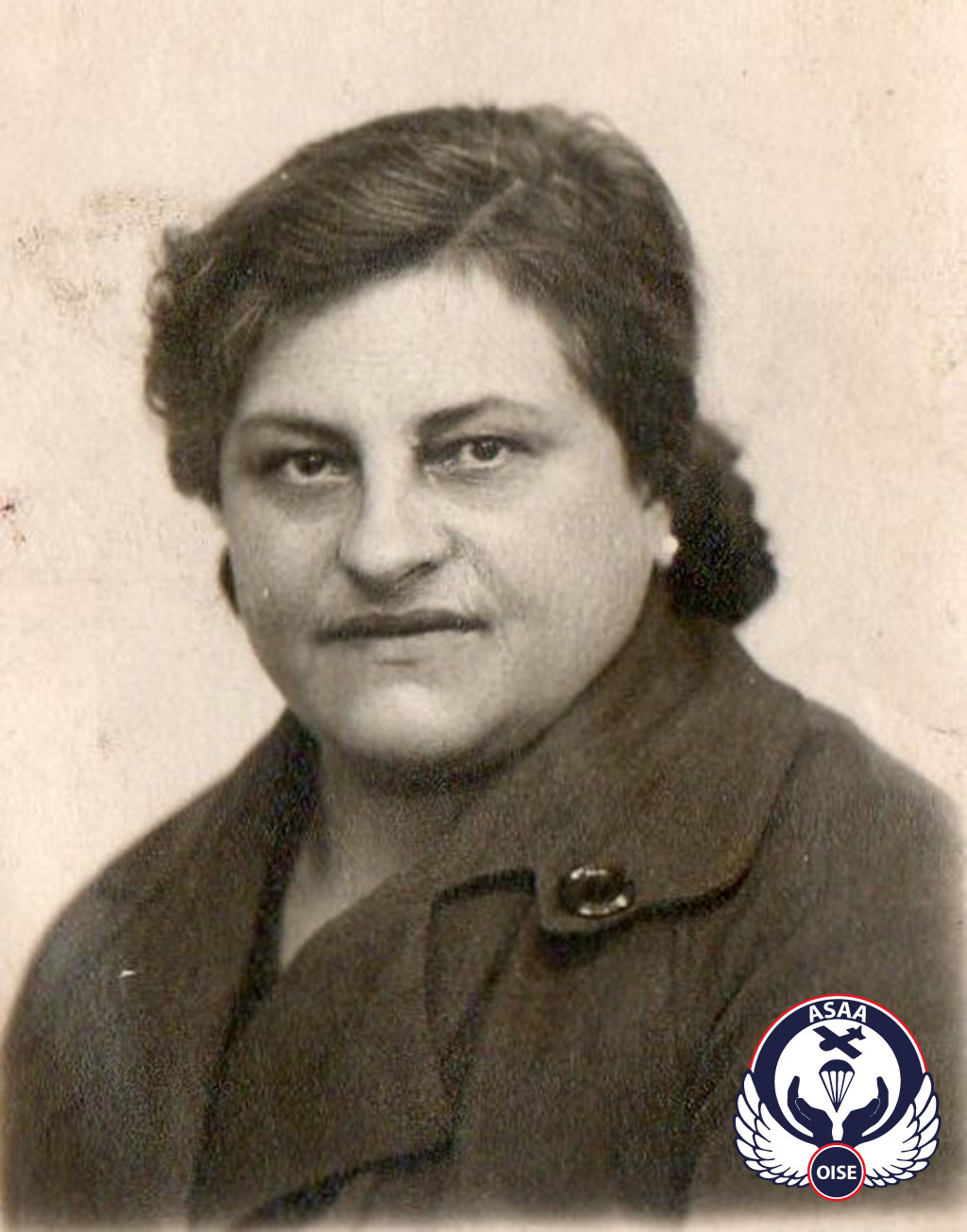

Omer and Eugenie Creton

F/Sgt. Eric L. Johnston fell onto the slate roof of a house in the hamlet of Vaux and sprained his ankle jumping from a height of several metres onto a cardboard box filled with empty bottles. He stayed in hiding until the morning and, at around 10am, asked for help from an unidentified Belgian farmer, who took him to his mother's house to treat his ankle. The next morning, 24 June, he was taken in by Roger Levasseur, a member of the local Resistance, who took him to the home of Germaine Carlier, a crossing-keeper, at Le Ployron, along the railway line between Compiègne and Montdidier, where he stayed only one night. On 25 June, Roger Levasseur cycled him to the home of Roger Floury, a teacher and town hall secretary in Montigny, who took him in for a few days before entrusting him to the care of Pierre Gager, an electrician employed by SICAE, who lived in Maignelay.

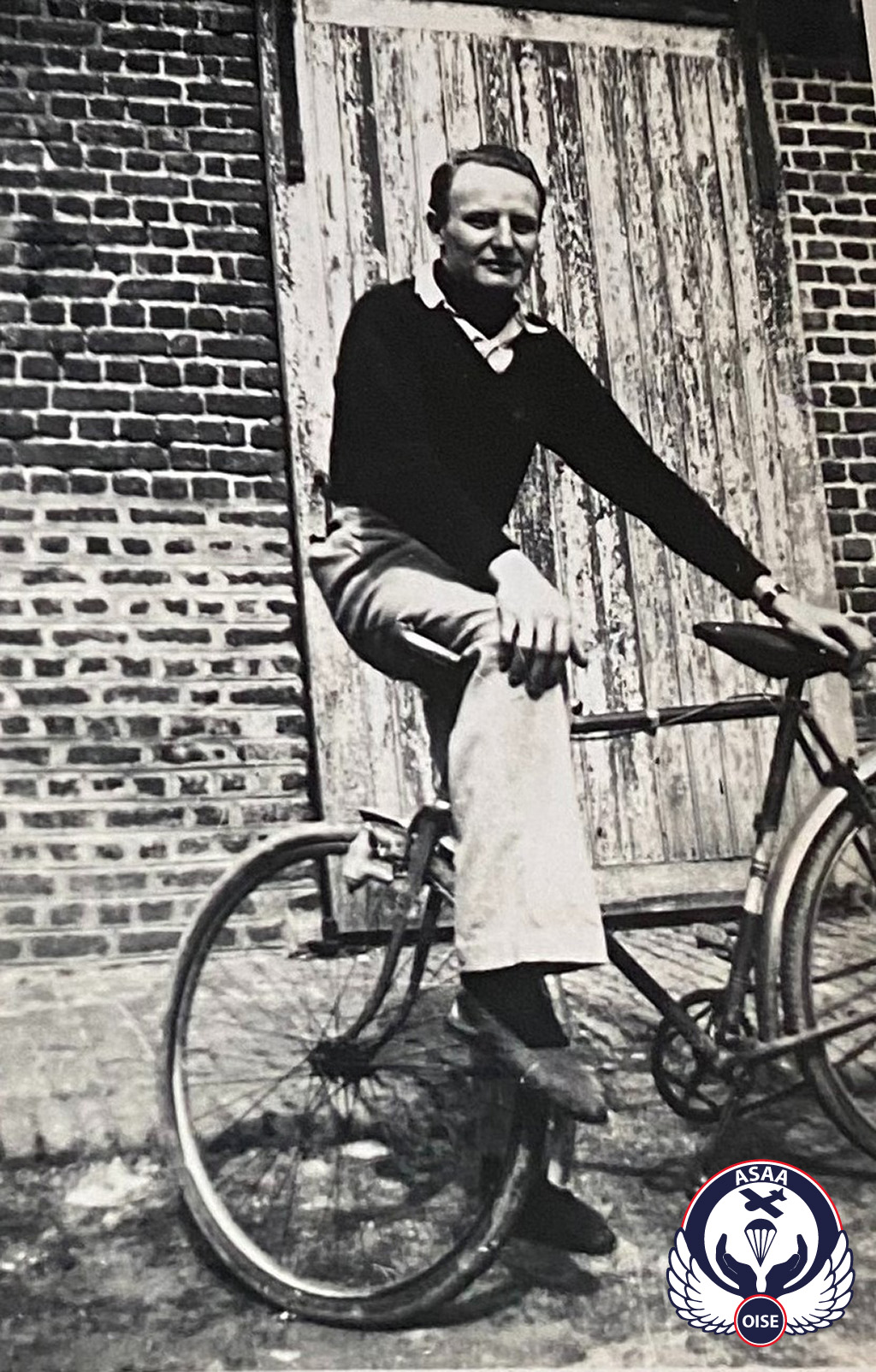

F/Sgt. Eric L. Johnston (NAA)

P/O Robert N. Mills fell in a wheat field and sprained his ankle near the village of Le Frestoy. Yves Dufeu came to his aid and took him to his parents' farm, where he was hidden in a barn. The next day, Pierre Gager, alias ‘Charles’ in the Resistance, came to collect him from René Dufeu's farm by bike and took him to his home in Maignelay. A few days later, he was joined by wireless operator Eric Johnston. The two airmen stayed with Pierre Gager until 8 July.

P/O Robert N. Mills (NAA)

F/Sgt. James P. Gwilliam landed in a tree near the hamlet of Le Tronquoy. For a moment, he was suspended from his parachute. Its straps were tangled in the branches and he was hanging upside down. After several attempts, he managed to free himself and fell heavily to the ground.

F/Sgt. James P. Gwilliam (NAA)

He then realised that he was missing a boot that he must have left behind before jumping out of the plane. The boot was stuck in the twisted metal of his turret. He was also wounded in the face and had lost several teeth. Sitting against a tree, he rested for a few hours and, at dawn, he headed for Le Tronquoy. He knocked on the window of a house and was taken in by a frightened but kind-hearted family. They offered him something to eat and his parachute was retrieved a little later by a resident of the house. With the family'concerns growing, he decided to head south on his own, to Cuvilly. He was then accompanied on his bike by a young boy who took him to Montdidier, where he stayed hidden for four days with an English schoolteacher. He was given shelter, food and civilian clothes. He was then put in touch with the Resistance.He spent several days in Le Ployron, at the home of Roger Levasseur and Germaine Carlier, on the edge of the railway line, where Eric Johnston had previously stayed.

F/Sgt. James P. Gwilliam during his evasion

He was visited by Pierre Gager who, unbeknownst to him, had previously hidden weapons under his bed. Pierre Gager took James Gwilliam to the home of a farming couple and then cycled shortly afterwards to Coivrel where he met Keith Mills at the café run by Omer and Eugénie Creton. Staying upstairs, the two airmen could often hear the voices of the Germans in the café below. Omer Creton would occasionally talk to them about his hobby of raising rabbits. The two airmen then stayed at school with Roland Horb and his wife Fernande, the village teacher.

After the German roundup in the Saint-Just-en-Chaussée sector, Robert Mills and Eric Johnston, brought by Pierre Gager, arrived in Coivrel on 8 July 1944 from Maignelay. They stayed temporarily at the Café Creton before being billeted with Paul Omnès. For around twenty days, although they were split between different families in the village, the four airmen met up often, trying to overcome boredom and inaction in the company of their hosts. They all had to stay indoors during the day and only came out in the evening to get some fresh air. Hosting airmen was a very risky situation, which could lead to the death penalty or deportation if discovered by the enemy.

Despite this threat, these courageous families worked hard for around twenty days to feed and pamper the four airmen in these times of restrictions and shortages. Albert Lherminier also gave them substantial help during this period.

On 28 July, the eve of the airmen's departure, these Coivrel residents went so far as to have their photographs taken with their protégés, thus immortalising this very special period.

Fernande Horb and her daughter Danièle, Keith Mills, Albert Lherminier, Eugénie Creton, Eric Johnston,

Robert Mills, Jeanne Bressolle, Paul Omnès and James Gwilliam.

(photo taken behind the house of Paul Omnès according to Eric Johnston)

On 29 July, after warmly thanking their hosts, the four Australian airmen prepared to leave Coivrel. They scribbled down their addresses, promising to write to each other or see each other again after the war. It was agreed that a coded message "The Kings are Crowned", to be broadcast on the BBC, would warn their hosts of their safe return to England.

Soon a lorry arrived, driven by Gaston Duriez who was in direct contact with Pierre Gager. It stopped in front of Paul Omnès's house. Robert Mills and Eric Johnston climbed into the back where two young Frenchmen were already sitting. A few streets further on, she stopped in front of the café. James Gwilliam and Keith Mills in turn piled in, each holding a bottle of wine.

They headed west while the six men at the back chatted happily and sipped from the bottles. Outside, the sun was shining and the atmosphere was almost festive. After these long days of waiting, and with a bit of luck, they would soon be back in England.

In the early afternoon, the four Australians left the vehicle just outside Chepoix, on the road leading to Breteuil. They were picked up by Guy Brillé, a young man of 19. Guy Brillé worked for a Resistance fighter named Robert Moulet, who had already organised the evacuation of other Allied airmen who had fallen in the area.

Accompanied by Guy Brillé, the four airmen set off on foot to a copse along the road. Unfortunately, Robert Moulet, whose intentions were good, had been tricked by two fake resistance fighters, Paul Villette and André Cauchemez, who were in fact working directly for the Germans. They had led Robert Moulet to believe that they had the means to evacuate the airmen by plane, which was pure deception.

The Australian airmen met up with Robert Moulet and Paul Villette in the grove. They waited about one hour for a new vehicle to arrive from Breteuil. The trap was sprung when the four airmen squeezed into the back of the vehicle, which restarted and set off towards Breteuil. A few kilometres further on, they were stopped by a German roadblock and greeted by machine-gun pointed at them. This was obviously no accident : the plan had been carefully organised. For the third time in three days, a total of 11 Allied airmen were arrested by the same men in the pay of the Germans.

A few days later, on 2 August 1944, the same traitors were behind the roundup in the villages of Tartigny and Bacouël.

Searched and handcuffed, the four airmen were taken that same evening to the Agel barracks in Beauvais and imprisoned in individual cells. For three days, they were interrogated and beaten to make them confess the names of the people who had come to their aid. None of them spoke, giving only their names, ranks and service numbers, thus avoiding further arrests.

Transferred to Fresnes prison, south of Paris, where they arrived on 2 August, they underwent further interrogation.

Faced with the imminent arrival of the Allied troops, the Germans decided to extract the prisoners from Fort de Romainville and Fresnes prison. On the morning of 15 August, Robert Mills, Keith Mills, Eric Johnston and James Gwilliam were taken by bus, along with many other prisoners, to Pantin, escorted by Milice and armed German soldiers. On the station's cattle platform, they were all brutally crammed into goods wagons (70 to 80 men minimum per wagon). With more than 2,200 men and women, including 169 Allied airmen, this last convoy left the Paris region at around 11pm, bound for Germany. It was the largest in terms of the number of deportees. During transport, on 18 August, P/O Joel M. Stevenson, of the Royal Canadian Air Force, managed to escape with two other prisoners through a hole in the floor of his carriage while the train was moving slowly. On several occasions, the French Resistance and the Red Cross tried to stop the convoy. Raoul Nordling, the Swedish consul, having negotiated an agreement with the Germans that placed the prisoners and deportees under his protection, also failed to stop the transport.

Finally arriving in Weimar at around midnight on 19 August, after five days of transport in appalling conditions and intense heat, the train was split up. After a night of waiting, the men's convoy arrived at the Buchenwald camp at around 9am on 20 August. The women's convoy reached Fürstenberg on 21 August. The women were then taken on foot to Ravensbrück concentration camp.

The 168 Allied airmen were held at Buchenwald until 19 October, when they were transferred to Stalag Luft III at Zagan (now in Poland), where they remained until 26 January 1945, when the camp was evacuated due to the Russian advance. After a forced march of around 80 km, Robert Mills, Keith Mills and Eric Johnston were held first at Spremberg and then at Stalag IIIA, near Luckenwalde, until its liberation on 22 April 1945 by the Soviet Army. The Soviet Army handed the prisoners over to the Americans on 6 May.

Separated from his crewmates and after several forced marches, James Gwilliam was sent to Westertimke, 30 km from Bremen, then to Trenthorst (near Lübeck) where he was liberated by the British Army on 1 May 1945.

October 2024 - Visit of the Johnston and Gwilliam families