22/23 June 1944

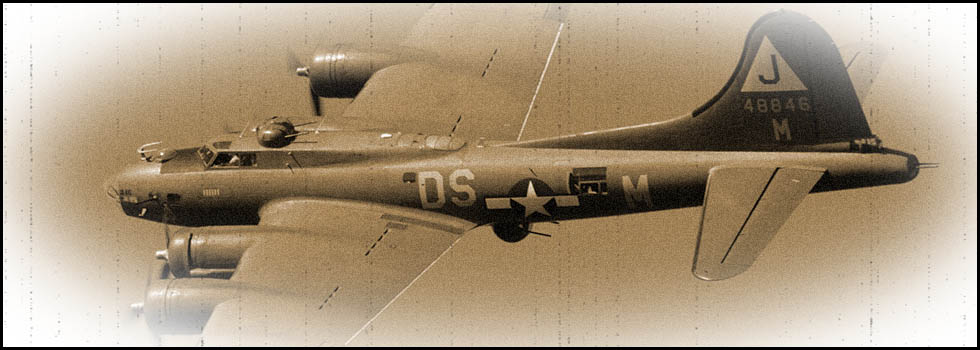

Handley-Page Halifax MkIII LK840

EY-J

RAF 78 Squadron

Quinquempoix (Oise)

Copyright © 2024 - Association des Sauveteurs d'Aviateurs Alliés- All rights reserved -

En français ![]()

For this night mission on 22/23 June 1944, RAF Bomber Command deployed 221 aircraft to bomb the railway installations at Laon (Aisne) and Reims (Marne).

Based in Breighton (Yorkshire), Squadron 78, equipped with Halifax bombers, was tasked with sending 24 crews to bomb the railway facilities in Laon. The aircraft took off at 10:48 p.m., assembled in formation and headed for France. The bombing, from an altitude of 11,500 ft, hit the railway centre but also part of the city that had already been severely damaged in previous raids.

That night, the crew of Halifax LK840 flew their 11th mission over French territory. During the return flight, at around 2 a.m., probably after being attacked by a German night fighter, the aircraft came down near the village of Quinquempoix.

During the same raid, Squadron 78 also suffered the loss of Halifax MZ692, which crashed in Rubescourt (Somme).

Crash site

The crew :

|

F/O David Lloyd IRWIN |

Pilot |

25 |

RCAF |

|

F/O Harold Arthur FUHR |

Navigator |

26 |

RCAF |

| Sgt. William Stanley SHARRATT |

Bomb aimer |

26 |

RAF |

|

Sgt. Alexander GILL |

Engineer | 26 | RAF |

|

F/O Brinley SHEPSTONE |

Wireless operator | 21 | RAF |

|

Sgt. William C. BROWN |

Mid-upper gunner |

29 |

RAF |

|

Sgt. Thomas Robert OWEN |

Rear gunner | 21 |

RAF |

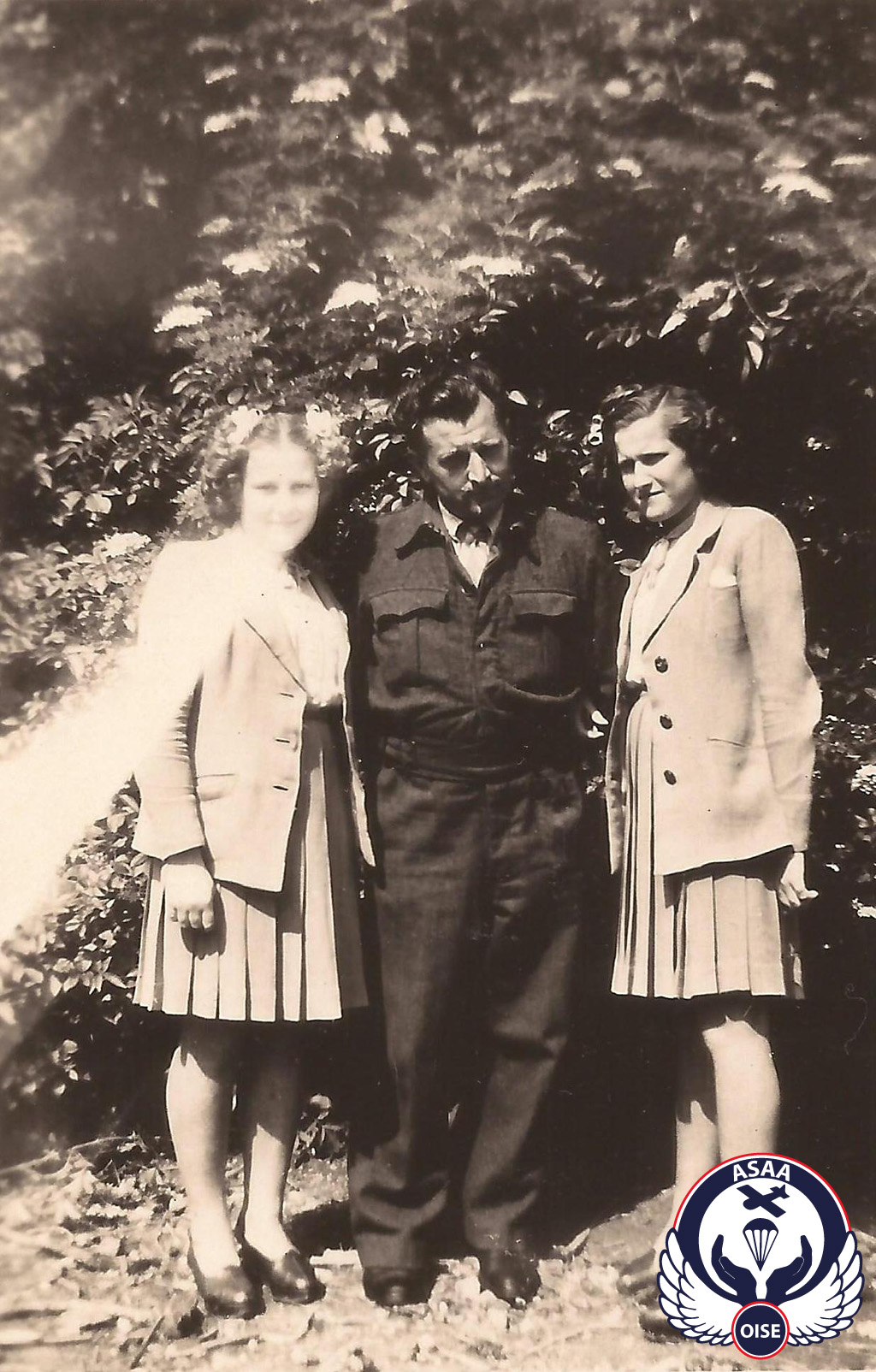

F/O David Irwin F/O Harold Fuhr

F/Os David Irwin, Harold Fuhr and Brinley Shepstone, as well as Sgt. Thomas Owen, perished in the crash. Sgt. Owen's bible was found among the wreckage.

Debris from the Halifax

Despite the German occupation, the four airmen were buried a few days later in the Quinquempoix communal cemetery in the presence of a large crowd who came to attend the funeral.

Sgt. Alexander Gill, wounded, was captured by the Germans and sent to a hospital for treatment before being transferred to a prison camp in Germany.

Sgt. William Sharratt managed to evacuate the aircraft and was taken in by Henri Vincenot in Wavignies, then by the Hennon family in the village of Ansauvillers. He stayed there for several days before being taken to the De Baynast family's Château de la Borde in Sains-Morainvillers, where he stayed for a day.

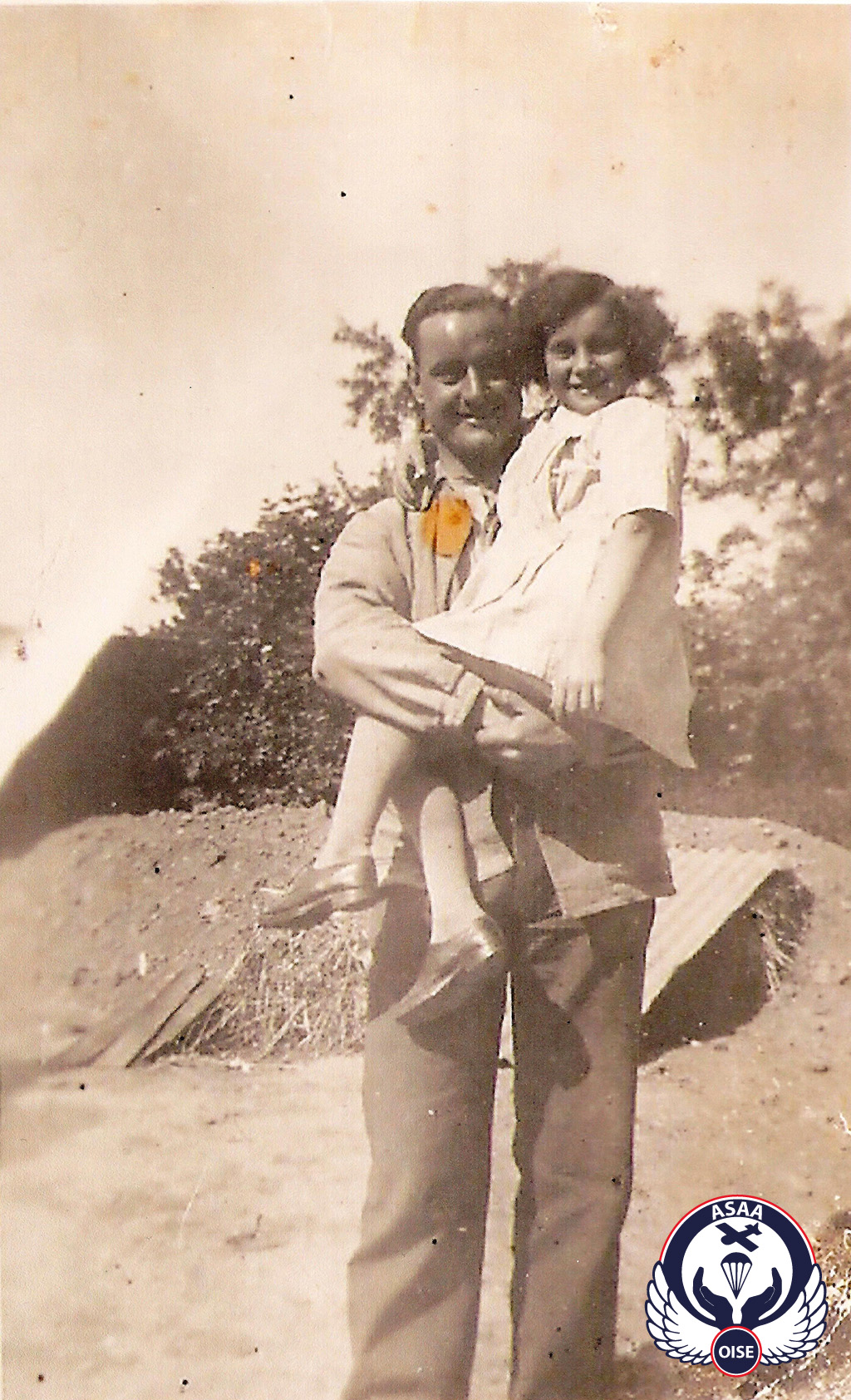

Sgt. William Sharrat with Michele Galopin Edmond Hennon in Sharrat's uniform

Fearing a search by the Germans (they had learned that their name was circulating in the offices of the Gestapo), Jacques and Colette de Baynast entrusted him to Robert Moulet, who took William Sharratt to the home of Miss Christiane Cauvel, a 33-year-old teacher who lived at the school in Le Mesnil-Saint-Firmin.

Sgt. William Sharratt was captured by the Germans in the school, probably because he had been denounced by someone looking for a reward. Christiane Cauvel, who had gone to get supplies, narrowly escaped arrest.

In the days that followed, he was transferred to Fresnes prison, near Paris. On 15 August 1944, along with more than 2,200 other prisoners guarded by the SS, he boarded a train on the cattle platform at Pantin station, bound for the Buchenwald concentration camp. In appalling conditions, the journey lasted five days. William Sharratt was one of 168 Allied airmen held in Buchenwald until mid-October 1944. Following the intervention of Luftwaffe officers, all the airmen were transferred to Stalag Luft III in Żagań, in eastern Germany, now in Poland. Faced with the advance of Soviet troops, the camp, which at the time contained thousands of prisoners, was evacuated at the end of January 1945. On foot or by train, during that harsh winter, the prisoners were sent to various other camps. William Sharratt was finally liberated by the American Army in May 1945.

Escape of Sgt. William Brown (based on his escape report and that of F/O Louis Greenburgh).

Sgt. William Brown, of Scottish origin, also managed to escape from the Halifax and landed in a wheat field not far from Wavignies at around 1.30am. He hid there until dawn and then approached a farm where the owners gave him food, civilian clothes and called for a doctor. At around 10 p.m., a doctor (possibly Edmond Caillard) came to treat him and then took him to Wavignies, to the home of Henri Vincenot, leader of the FTP group, and his wife Yvonne, caretakers of Wavignies castle. They had already been sheltering two other British airmen, Richard Woosnam and Fred Carey, since 10 June.

F/Sgt. Richard Woosnam and Sgt. Fred Carey were members of the crew of Lancaster LL727, Squadron 514, shot down on the night of 7/8 June 1944 at Sainte-Eusoye (Oise).

On 29 June, F/O Louis Greenburgh, who had been staying with Paul Grenaud at Puits-la Vallée for three weeks, was taken in a horse-drawn cart to the Vincenot family home.

F/O Louis Greenburgh was the Canadian pilot of Lancaster LL727 who fell at Sainte-Eusoye on the night of 7/8 June 1944.

Henri Vincenot

On 1 July, brought by Yvonne Vincenot, William Brown and Louis Greenburgh came to stay with Henri Réant, a 65-year-old town hall secretary in Wavignies, and his wife Marie. The two airmen stayed in the cellar during the day and slept in the attic at night.

On 2 July, on the advice of Lucien Sueur, mayor of Wavignies, Henri Vincenot, who sensed imminent danger, entrusted F/Sgt. Richard Woosnam and Sgt. Fred Carey to Joseph Bugar, a farm labourer of Yugoslav origin, and his companion Maria Dubezak.

Early on the morning of 3 July, the Germans invaded the village. The Réant family was woken by the sound of gunfire in the village. Richard Vanach, a Belgian living in Wavignies, came to warn the Réants that the Germans had attacked the château and surrounded the village. During the engagement with the enemy, Henri Vincenot was killed in the presence of his wife and two children, aged 6 and 8.

The Réant family quickly hid William Brown and Louis Greenburgh under faggots in a barn adjoining their home. Marie Réant then asked them to come out and guided them out of the house. The two airmen hid in nettles all day. In the evening, she sent a child who brought food and a compass, and the child's father helped them get away from the village.

The Germans came to search the house but had not managed to find the two airmen. They arrested Henri Réant, who was taken to Compiègne prison and then, from 24 July, to the Royallieu camp. On 17 August, he was deported to Buchenwald concentration camp. On 14 September, he was part of the convoy that took some of the deportees to the Neu-Stassfurt salt mines. Exhausted and ill, Henri Réant died there in early 1945.

That same morning of 3 July, the Germans came to search Joseph Bugar's home for the two airmen, Richard Woosnam and Fred Carey, who had meanwhile been hiding in a hole under a dung heap. They were eventually discovered and taken to the chateau, where a number of residents had already been arrested. All were then taken to Compiègne prison, where they were incarcerated.

Richard Woosnam and Fred Carey were sent to Stalag Luft 7 and then to Stalag 3A in Germany. They were liberated by the Soviet Army in April 1945.

Maria Dubezak was deported to Ravensbrück and then to Bergen-Belsen, where she survived. Imprisoned, Joseph Bugar escaped deportation. Schoolteacher Jean Dupuy died in Buchenwald in February 1945. Lucien Sueur and other villagers arrested during the round-up survived the hell of the concentration camp.

Now on their own, William Brown and Louis Greenburgh took advantage of the darkness to head south, travelling mainly at night, crossing fields and villages while obtaining food from complaisant farmers. On 11 July, they reached the hamlet of Fillerval, near the village of Thury-sous-Clermont. A little girl of around twelve was drawing water from a well when she spotted the two frightening-looking men, dressed in rags and unshaven for several days. Frightened at first, she realised after a brief exchange that they were Allied airmen on the run and went to tell her parents. They were Aurélien and Fernande Fouquet. Welcomed into the house, the woman prepared a meal and the two airmen were able to enjoy a good bath and were given new clothes. They could wander around the house but had to hide in the cellar at the slightest alarm. They felt like part of the family, spending their time playing cards or draughts. Aurélien and Fernande Fouquet planned to keep them with them until the Liberation, but a member of the Resistance talked them out of it and decided to move the two airmen.

A few days later, they were taken by car to Mouy, to the home of Joseph Balandras, who owned a garage. Despite the presence of German soldiers who regularly came to have their vehicles repaired, Joseph Balandras took the risk of sheltering the two airmen in a room adjoining the workshop for two days.

William Brown, still with Louis Greenburgh, was then taken in a cart through a wood to the house of Gaston Coyot, a gamekeeper who lived in the hamlet of Saint-Claude, near Bury. The two airmen stayed in the attic for a fortnight, under the protection of the Coyot family. During their stay, the Germans undertook a search for Resistance fighters who had carried out sabotage, forcing the two airmen to hide in a cave for three days as a safety precaution.

Around 21 July (around 1 August according to Greenburgh), Joseph Balandras took the two airmen by car to Chantilly, where a rendezvous was arranged with a young woman (possibly Yvonne Deplanche) who took charge of them. Following her at a distance, the two airmen reached Chantilly station, where there were many German soldiers. Tickets in hand and accompanied by their guide, they boarded a train partly filled with German troops bound for Paris.

Once they had arrived at the Gare du Nord and passed through the checkpoints without a hitch, the young woman took them to Renée Picherie's house in the 17th arrondissement, rue des Epinettes, their new hostess. After a good meal, the two airmen fell asleep. They stayed at this address for 5 days.

Occasionally, Mrs Picherie would take them on a “sightseeing” tour of the capital. However, one of these visits almost went wrong. Walking near the Butte Montmartre, William Brown, who was a few metres behind, was approached by two German officers. Knowing that the airman spoke no French and had no papers, Mme Picherie coolly approached the Germans, asking them what they wanted. The Germans were suspicious of Brown, who didn't answer them. Renée Picherie feigned hysteria, saying that her brother was deaf and dumb, asking the Germans what they had done for him and what had happened to the French since the Occupation. The two officers, bewildered, took her for a madwoman and walked away.

The two airmen were subsequently provided with false identity papers and separated.

A few days later, Sgt. William C. Brown was taken to Austerlitz station and sent to one of the camps in the Fréteval forest in the Loir-et-Cher region. Since the Allied troops had landed in Normandy, there was no longer any question of evacuating Allied airmen via the escape routes leading to the Spanish border or Brittany.

More than 150 airmen were held in these camps until they were liberated by American troops on 14 August 1944.

During his evacuation towards Le Mans and then Bayeux, the lorry in which William Brown was travelling swerved and overturned, injuring Brown in the wrist. He was repatriated to the UK a few days later and treated at St Athan's Hospital in Wales.

7 June 2025 - Ceremony in memory of the crew of Halifax LK840